Subscribe

Data delivered to your inbox. Keep up with the latest developments.A telecom provider used inauthentic pages to discredit its competitors.

On February 12, 2020, as a part of a larger takedown, Facebook removed 13 accounts and 10 pages linked to MyTel, a Burmese telecommunications company indirectly owned by the Myanmar and Vietnamese militaries, for engaging in “coordinated inauthentic behavior.” Of the 23 total assets within the Burmese set, the DFRLab had access to six of the pages prior to the takedown. These six presented themselves as neutral special interest pages focused on mobile technology but targeted the commercial opponents of MyTel and its sister company, MyTelPay, as well MyTel competitors’ users.

This operation differed in one respect from previous commercial operations the DFRLab has encountered, such as the May 2019 takedown of assets related to the Israeli political marketing firm Archimedes Group and the December 2019 takedown of assets linked to Panda, an advertising agency in Georgia working on behalf of the Georgian government. While the actors in those earlier cases were profit-driven contracted services, they acted on behalf of a client. In the case of MyTel, it appeared that the pages linked to the telecommunication company were taking aim at the company’s own competitors as an indirect means of boosting its own brand and profit, rather than by selling “disinformation-as-a-service.”

In its announcement of the takedown, Facebook said:

The Page admins and account owners typically shared content in English and Burmese about alleged business failures and planned market exit of some service providers in Myanmar, and their alleged fraudulent activity against their customers. Although the people behind this activity attempted to conceal their identities and coordination, our investigation found links to two telecom providers — Mytel in Myanmar and Viettel in Vietnam — and Gapit Communications, a PR firm in Vietnam.

The DFRLab’s investigation found that the assets displayed several characteristics that pointed to coordinated activity, including similar post formatting conventions, identical content published within short timeframes of each other, and page administrators based in Vietnam and Myanmar. They also displayed evidence of inauthenticity, as they initially appeared set up as neutral special interest pages, and some may have artificially amplified their page likes.

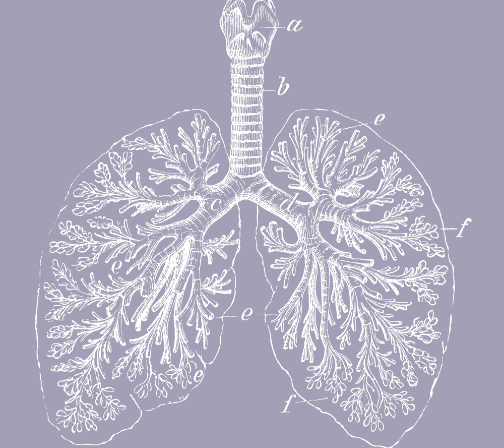

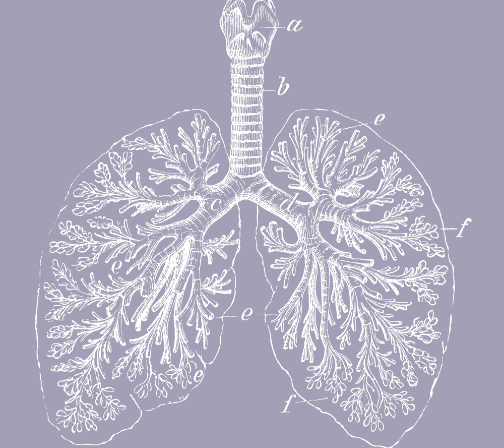

Myanmar’s telecommunications sector

Myanmar is a late, but meteoric, entrant to the telecommunications sector. In 2011, the mobile penetration rates in the Southeast Asian country was sitting at only 2 percent, but after the government dismantled a monopoly held by the state-owned telecoms firm Myanmar Posts and Telecom (MPT) in 2013, the situation changed drastically. Additional operating licenses granted to Norway’s Telenor and the Qatar’s Ooredoo fostered competition and drove down communication costs and barriers to entry, and by 2018 Myanmar had more active sim-cards than citizens. Its mobile penetration rate of 80 percent edges out even developed countries like Germany (78.8 percent) and the United States (77 percent).

The surge in mobile phone use has also seen an increase in the use of mobile payment providers. Small grocers and supermarkets act as mobile payment agents, essentially replacing traditional ATM’s in the Burmese economy.

MyTel, a joint venture between commercial entities controlled by the Vietnamese and Burmese militaries, along with private conglomerate MNTH, was granted Myanmar’s fourth operator’s license early in 2017.

MyTel also launched its own mobile payment solution in June 2019, called MyTelPay, which tapped into its existing mobile phone userbase.

The assets

The network consisted of six assets posing as neutral special interest pages with a focus on mobile technology and lifehacks. None of the pages disclosed any affiliation with MyTel.

Some of the pages started out on a very patriotic and nationalist tone, possibly to garner support for the fledgling pages shortly after their creation. Gradually, the pages shifted to content promoting the MyTel brand.

The two largest assets, “Myanmar Internet & Telecom News” and “Myanmar Telecom Promotions,” also presented neutral content, as well promotional material for MyTel’s competitors, in a possible effort to cast doubt on the pages’ objective.

Over time, the six pages accumulated slightly more than 290,000 page likes. A CrowdTangle analysis of the pages in the network indicated that four of the pages showed suspicious increases in the number of page likes when plotted over time. “Page likes” refers to a measure of the popularity of the page and is a direct reflection of the number of users that opt-in to receive posts from the page on their timeline.

The uptick in page likes occurred around the same time as an uptick in page interactions, a cumulative term for likes, shares, and comments on posts the page authored. Furthermore, these interactions ceased just as rapidly as they commenced. In the incidents highlighted in dark blue and green in the image above, the page likes continued to increase for days, after page interactions had ceased, but abruptly plateaued soon after. This pattern indicated that the pages’ like counts may have been artificially boosted.

In the case of Myanmar Internet & Telecom News, it saw exponential growth in page likes before it ever posted any content. The increase in page likes started on December 23, 2018, a few days before the increase in page interactions seen on December 28, 2018 — this preemptive engagement is another indicator of inauthentic behavior.

Page administration and history

The Page Transparency section for each of the assets provided an indication of possible coordinated activity.

First, four of the six pages — in two pairs — had creation dates clustered around two separate days, with two created on December 14, 2018, and another two on March 7, 2019.

In addition to being created on December 14, 2018,Myanmar Telecom Promotions and Myanmar Internet & Telecom Newswere also renamed from their original page titles on the same date: March 10, 2019.

The pages Myanmar Knowledge and Smart Life for Myanmar also shared a creation date: March 7, 2019.

Second, the page administrators for most of the assets were based in the same two countries: Vietnam and Myanmar. The only exception was the newest page in the network, Myanmar People Voice, which elected to not display the location of its page admins. MyTel’s official Facebook pages also had admins in Vietnam and Myanmar.

Examples of campaigns

In several instances, the pages shared identical content to one another as part of what appeared to be a series of campaigns critical of Ooredoo, Telenor, and MPT, MyTel’s direct competitors in the telecommunication sector.

“Wave Money”

On January 20, 2020, all six assets in the network published a post critical of Wave Money, a mobile payment platform operated by MyTel competitor Telenor. The post featured a meme that depicted Wave Money as comparable to “expert-level bank robbery.” Wave Money is a direct competitor to MyTel’s payment platform, MyTelPay.

To determine the sequence and timing of these posts, the DFRLab looked at the source code of the site. Facebook’s timestamps are not granular enough to determine the exact second of the post, but the UNIX timestamp found in the source code of each post is.

The UNIX timestamp is a measure of the number of seconds that have passed since 00:00 on January 1, 1970, and is useful to describe a specific, timezone-agnostic moment. The UNIX value can be converted into human-readable date and time values using a spreadsheet formula or various converters found online.

After converting the UNIX timestamp back into a human readable date, the posts could be catalogued down to the second.

Smart Life for Myanmar published the first post against Wave Money, on 11:35:22 UTC. Over the next three minutes, the other five pages in the network replicated the post on their respective pages.

Notably, none of the pages “shared” any posts published by the other assets in the network, despite the content being identical. Instead each page copied and published the Wave Money post as an original post. This points to an element of subterfuge: the page administrators wanted to drive the Wave Money narrative but may have hoped to avoid any associations and links between the assets pushing the content.

The *31# Campaign

On October 19, 2019, all six assets published a sequence of photos that promised mobile phone users 10 gigabytes of data if they dialed the code “*31#” from their phones. These images were stylized to resemble the major mobile operators in Myanmar.

The provided code, however, was a “man-machine interface (MMI)” code, which are used to access hidden options on the handset when they are entered. When dialed, the *31# code disables a handset’s outgoing caller identification function. According to users in the comments of these posts, as well as some online forums, this had the secondary effect of also blocking the user from making any calls on the Burmese network using that handset.

Conveniently, MyTel’s official Facebook page posted a solution to this problem a day before the assets ran the “promotion.” By dialing #31#, caller identification would be reenabled on the device and service restored… thanks to MyTel.

The UNIX timestamps found in the source code for these posts indicated that the *31# campaign was sent out in two batches. Four of the assets published these posts between 03:01:08 UTC and 03:10:12 UTC on October 19, 2019.

Three hours later, all six pages published a second round of similar posts between 06:05:19 UTC and 06:09:03 UTC.

Shared posting conventions

In another indication of coordination, the pages posted content with typographical similarities. Some of the posts, for instance, contained text in triplicate, with demarcated sections posted in “English,” “Unicode,” and “Zawgyi.”

The Burmese alphabet has historically been type-faced using the Zawgyi font, a set of non-compliant Unicode characters that was used as a stopgap to encode the alphabet into electronic text. A Unicode-compliant version of the character set was adopted by Myanmar in 2019 but is still being phased in. By using three types of characters, the page administrators ensured that the posts were readable by as large an audience as possible.

At least three of the assets in the network shared this strategy, which the official MyTel and MyTelPay Facebook pages had also adopted.

Conclusion

The examples provided above are representative samples taken from the pages in the network while they were still active. A much larger corpus of analysis informed these conclusions. Considered in isolation, any one of these links could easily be disregarded as mere coincidence. Taken together, however, each disparate example reinforced the links between MyTel and this network of inauthentic pages.

Jean le Roux is a Research Associate, Southern Africa, with the Digital Forensic Research Lab and is based in South Africa.

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.

The Digital Forensic Research Lab team in southern Africa works in partnership with Code for Africa.