Subscribe

Data delivered to your inbox. Keep up with the latest developments.South Africans have been targeted by a rehashed “free voucher” scam by linking it to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Planet49, a Hong Kong-based digital marketing company with close associations with Asia Pacific Marketing Limited, targeted South African users with a digital marketing campaign intended to harvest their personal information. The campaign falsely presented a COVID-19 “relief promotion” by local grocery chains. In reality, it enticed WhatsApp users to not only share the promotion with several of their WhatsApp contacts, but also consent to Planet49 selling their personal information to third parties.

The grocery chains referenced in the campaign have denied any involvement with Planet49.

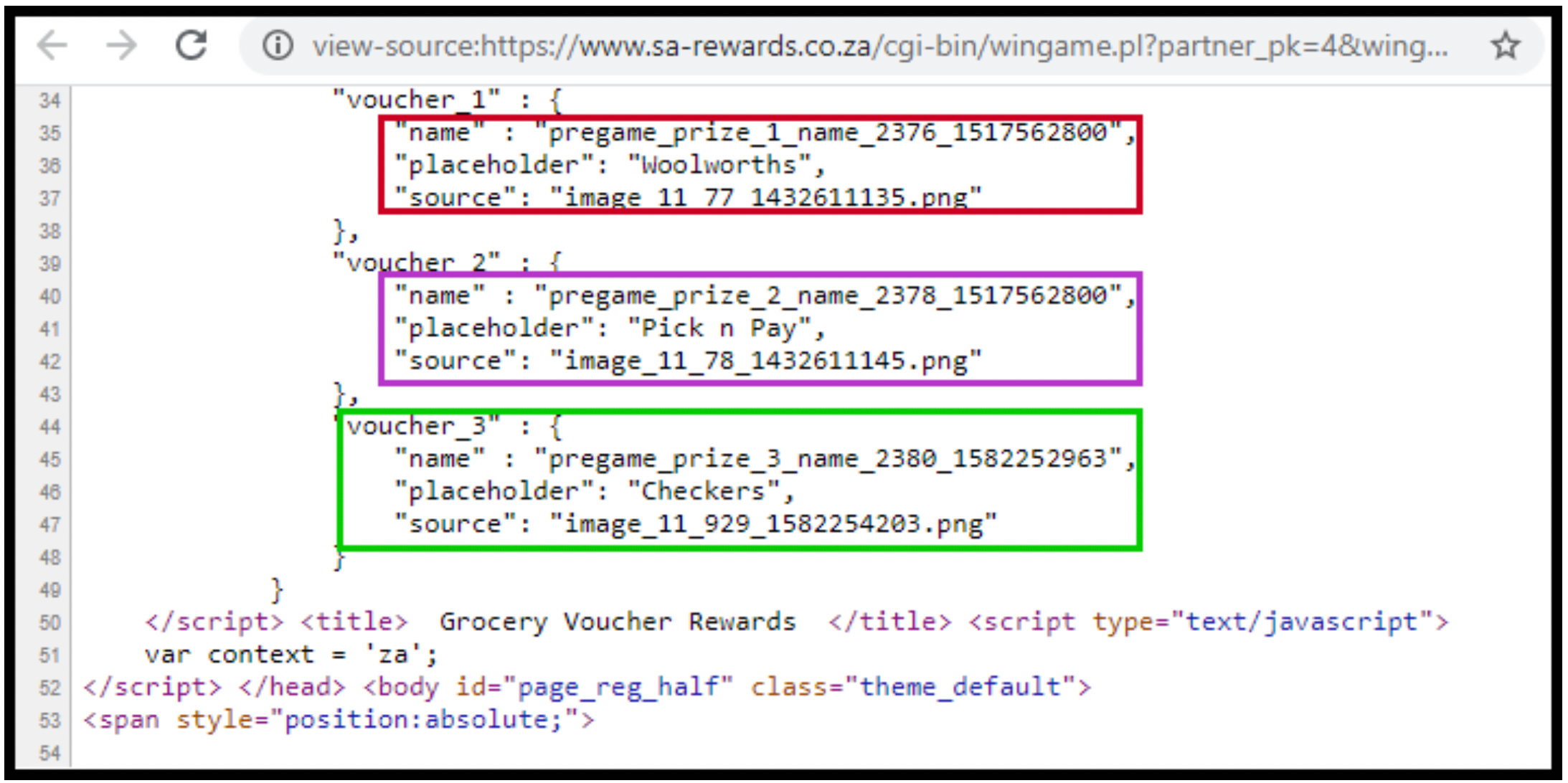

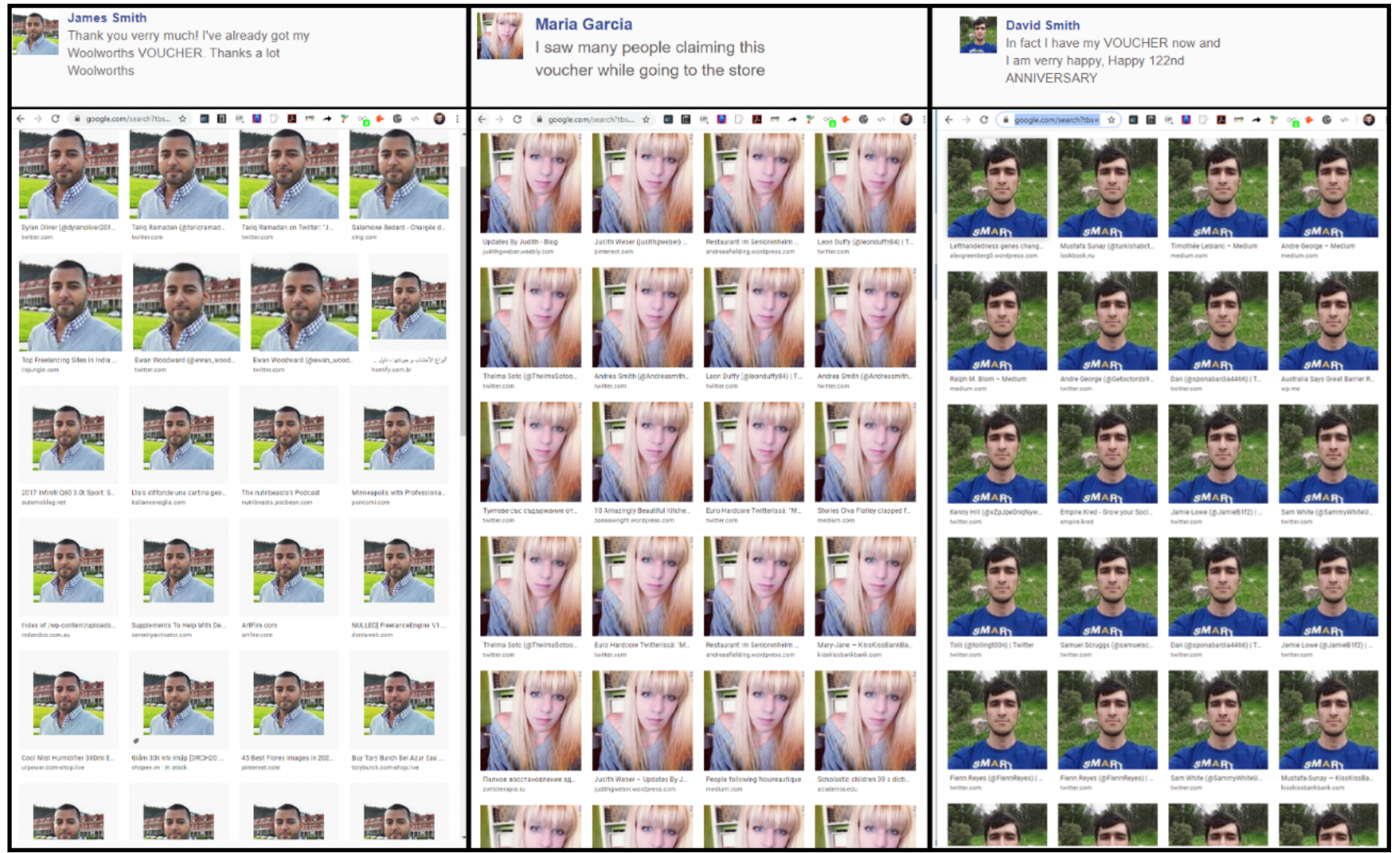

A DFRLab investigation analyzed the source code of these websites, which revealed the links to a Planet49 website registered in 2014. The website had fabricated a Facebook-style comments section using an API for randomly generating profiles pictures. Reverse image searches revealed that these profiles pictures were used prolifically across social media, blogging platforms, and review platforms on other websites.

There is also evidence that some of these campaigns were used in Australia as well.

Planet49 registered the www.sa-rewards.co.za domain in May 2014. Less than a year later, the first warnings against the website and its fake voucher lotteries began circulating online. In 2019, Planet49 was reprimanded by the European Court of Justice for transgressing GDPR requirements in its online lotteries. Meanwhile, crucial sections of South Africa’s Protection of Personal Information (POPI) Act, meant to be the country’s parallel to GDPR, are still in limbo since some sections of the POPI Act were promulgated six years ago.

The website

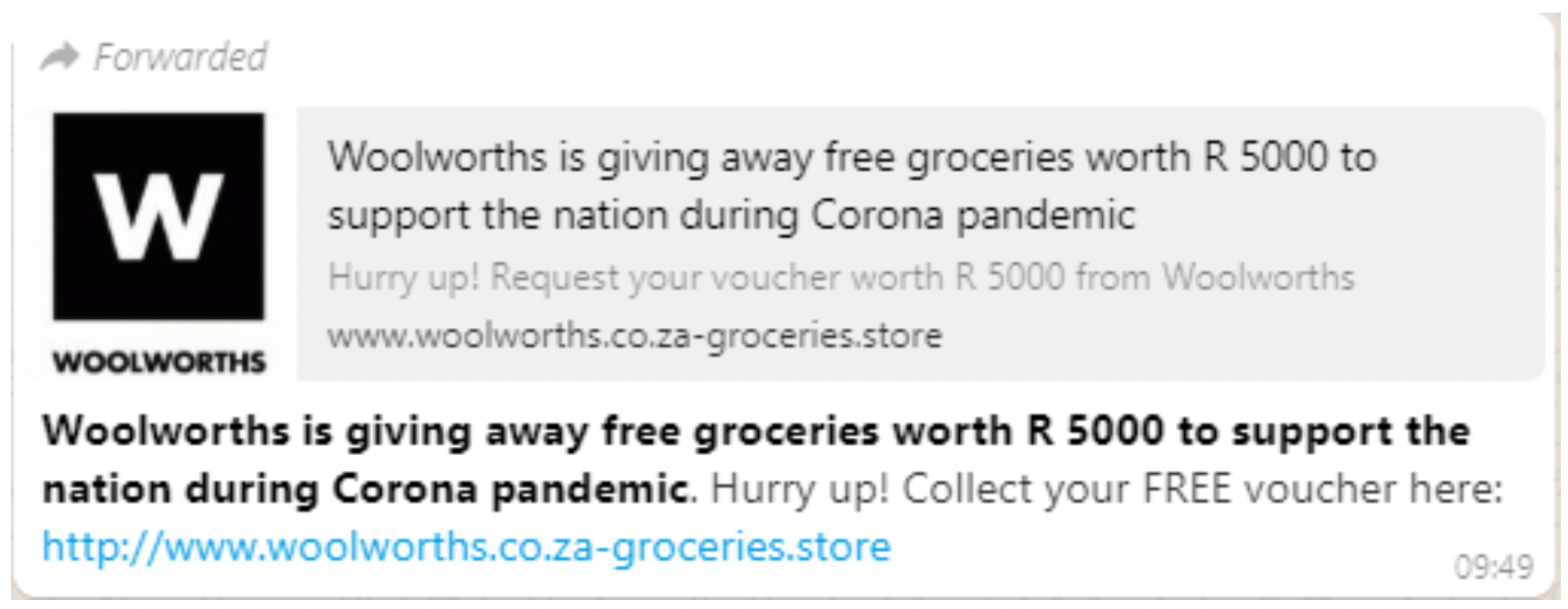

The campaign spread mainly via a short WhatsApp message that contained a link to a seemingly legitimate website for one of South Africa’s grocery chains.

This message was deceptively styled to mimic the official Woolworths website, and gave the impression that Woolworths was giving away R5 000 ($280) worth of groceries for free as part of a coronavirus support program.

Once a user clicked on this link, a two-stage process commenced.

Firstly, a landing page (woolworths.co.za-groceries.store) enticed the user into sending the same WhatsApp message containing a link to the website to several of their contacts. This landing page changed twice during the course of the DFRLab investigation, but the content remained identical. It did this by taking the user through a short survey before prompting them to send the link to at least 10 of their contacts. A counter would keep track of the number of times a user shared this with their friends or groups.

These steps could be discerned from the JavaScript functions embedded into the buttons.

Once the threshold was met, it would allow the user to click through to a second website, www.sa-rewards.co.za. This website was registered to Planet49, and required the user to enter their personal details, and consent to Planet49 processing and selling this information to third parties for marketing purposes, before they could secure an entry into the draw.

This process ensured that users propagated the website to several of their WhatsApp contacts before they even entered the drawing by providing their personal information.

This coronavirus “promotion” was deceptive. The domain names were crafted in such a manner that they mimicked Woolworths’ official domain, and official logos were used to give the impression that the campaign was sanctioned by Woolworths. The mention of the coronavirus kept the campaign-which seems to have been running since 2016-fresh.

A dive into the source code of the www.sa-rewards.co.za website revealed that in addition to Woolworths, the campaign also targeted two other grocery chains, Pick&Pay and Spar. The site would be tailored to either Woolworth, Spar, or Pick&Pay shoppers depending on the link you received.

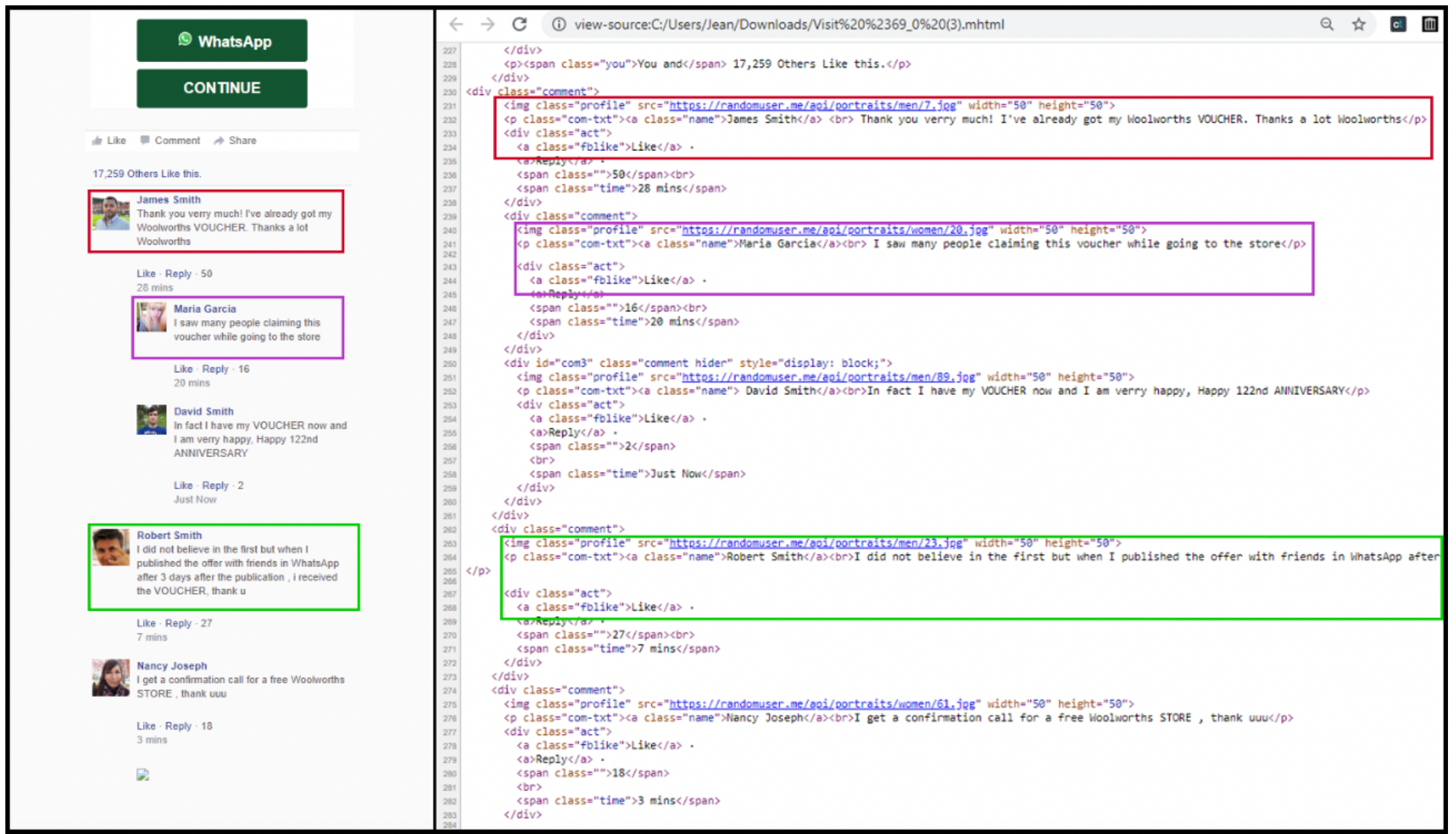

Another deception was the way in which a portion of the website was designed to imitate a Facebook comments section. This featured several happy “participants” expressing their satisfaction at receiving their vouchers, despite the drawing date only being slated for June this year.

The source code, however, revealed that this was fake. The Facebook comments section was hard-coded into the website, and was made to imitate real users’ comments and likes. The source code also showed that the “user profiles” were being generated automatically using an API built specifically to generate random user accounts.

Reverse image searches of these photographs revealed that scores of websites used the same profile pictures on their websites. These included customer reviews for a gaming-sales website in Germany, a WordPress management tool, and even hidden unused in the source code of the website for a UK based dentist.

Iterations of this “free voucher” scam has targeted South African users since 2014. In a country rife with unemployment and inequality, the promise of a substantial voucher in exchange for personal information seems enticing. Now, with a nationwide lockdown in effect in South Africa in an attempt to curb the spread of the virus, the scammers’ angle of attack has shifted to keep the old scam current.

Jean Le Roux is a Research Associate, Southern Africa, with the Digital Forensic Research Lab and is based in South Africa.

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.

The Digital Forensic Research Lab team in southern Africa works in partnership with Code for Africa.